Understanding educators’ well-being

One of the desires of any parent or caregiver is to provide the best educational experience for their learners. While this is a worthwhile aim, it is important to take cognisance of the processes and actors involved in ensuring quality education, one of these being the educator. The success of learners and adequacy of learning experiences are largely driven by the educators that have frequent contact with these youngsters.

In educational and school settings, scholarly well-being research tends to have a skewed focus on building psychological strengths and reduction of problematic behaviours among learners (to the neglect of educators) with interventions targeted towards educators mostly tailored to improve learner outcomes. Additionally, although there is evidence for enhancing positive functioning among educators, such research has been limited to workplace domains and not overall positive functioning in different life domains. Research on positive functioning among educators across life domains is necessary for managing relationships in the classroom setting and ensuring learner success1. In understanding educators’ well-being, it is important to highlight not just risk factors but also resources that might enhance well-being. Hue2 identified seven competencies including self-knowledge, self-esteem, emotional control, motivation, knowledge of others, valuing and leadership that served as internal resources for educators. In this opinion piece, I reflect on the current gaps in research on educators’ well-being, and highlight the importance of well-being promotion and the factors necessary for the enhancement of well-being of educators.

Educators’ well-being encompasses all areas of health-related quality of life of educators and individuals working directly with learners within an educational context. Well-being as a positive mental state is characterised by positive functioning and feeling well3,4. This is traced back to historical roots of eudemonia (“a life well-lived”) and hedonia (experience of pleasure and positive emotions) in the work of Aristotle (350 BC) and other philosophers. Studies exploring the well-being of educators have not clearly differentiated these aspects of well-being and tend to focus mostly on positive functioning. In well-being research, the focus on positive experiences has led to the proliferation of studies that explore resources that educators draw from to enhance their well-being. Commonly noted are self-efficacy5, self-beliefs6, optimism7, self-determination8, need satisfaction and personal characteristics9. Central to educators’ well-being is the need for feelings of capability within their domain of work. This is because internalised notions of their ability to effect changes in the lives of learners and tackle difficulties seemed to be a determinant factor in the measurement of satisfaction of educators’ lives.

Ensuring educators’ well-being is necessary for enhancing learners’ achievements10. This is because educators serve as knowledge mediating tools and play the role of helping learners to experience a sense of belonging in school as well as develop trusting adult relationships. This implies that educators do not only teach content, but nurture positive relationships11. Educators are among the first non-parental adult role models that provide a platform for the shaping of a child’s social skills12. The educator assists in equipping learners for the future by motivating and providing assistance to those under extreme stress13. Educators could serve as a protective factor for children who are at risk for academic failure14.

The increasing expectations placed on educators to ensure success of learners has resulted in most educators reporting that they regarded teaching as stressful, leading to a high level of burnout in this group. One of the leading causes of stress is the inability of educators to deal with learner misbehaviour and pressures for increased accountability related to learners’ test scores amidst limited resources available for educators. All of these factors can initiate negative emotions and hinder the educator’s capacity for high-quality instruction15. Educator attrition rates have been reported as quite high in the USA16. Hall-Kenyon17 argued that educator well-being was confronted by challenges including levels of compensation, levels of education, job satisfaction and stress.

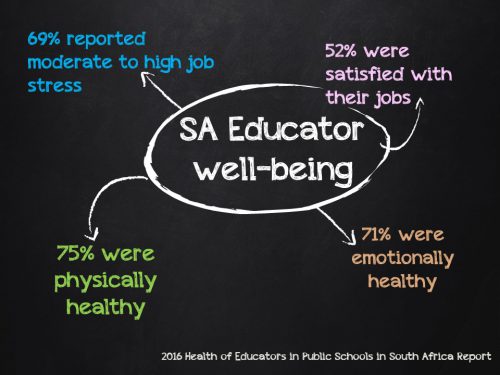

The 2016 Health of educators in Public Schools in South Africa [Link] study found that although a high proportion of educators reported being physically or mentally healthy, only around half of respondents were satisfied with their jobs. In this context, promoting educators’ well-being is necessary for a number of reasons. Apart from the need to enhance well-being in its own right through interventions, there is an increase in the ability of educators to effectively engage with learners and reduce stress and tendencies for burnout.

Other learner outcomes have also been linked to educators’ well-being including improved motivation and reduction of problematic behaviours. Educators are not only faced with work-related challenges like any other occupation, but also unique work contexts in which their experience of well-being is necessary for the learners they work with. In South Africa, both a practical and policy response in the form of programs targeted at evaluating and improving educators’ well-being is paramount as well as providing resources to combat challenges faced.

Author: Dr Angelina Fadiji, Post Doc Fellow

Education and Skills Development research programme of the HSRC

References

- Jackson, L., & Rothmann, S. (2005). Work-related well-being of educators in a district of the North-West Province: research article: general. Perspectives in Education, 23(1), 107-122.

- Hue, M. T. (2012). Inclusion practices with Special Educational Needs students in a Hong Kong secondary school: teachers’ narratives from a school guidance perspective. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40(2), 143-156.

- Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social psychology quarterly, 121-140.

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology, 57(6), 1069.

- Zee, M., de Jong, P. F., & Koomen, H. M. (2017). From externalizing student behavior to student-specific teacher self-efficacy: The role of teacher-perceived conflict and closeness in the student–teacher relationship. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 37-50.

- McInerney, D. M., Ganotice, F. A., King, R. B., Morin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2015). Teachers’ Commitment and psychological well-being: implications of self-beliefs for teaching in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 35(8), 926-945.

- Desrumaux, P., Lapointe, D., Sima, M. N., Boudrias, J. S., Savoie, A., & Brunet, L. (2015). The impact of job demands, climate, and optimism on well-being and distress at work: What are the mediating effects of basic psychological need satisfaction?. Revue Européenne De Psychologie Appliquée/European Review of Applied Psychology, 65(4), 179-188.

- Ricard, N. C., & Pelletier, L. G. (2016). Dropping out of high school: The role of parent and teacher self-determination support, reciprocal friendships and academic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 44, 32-40.

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2011). Predicting teacher commitment: The impact of school climate and social–emotional learning. Psychology in the Schools, 48(10), 1034-1048.

- Frank, J. L., Reibel, D., Broderick, P., Cantrell, T., & Metz, S. (2015). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on educator stress and well-being: Results from a pilot study. Mindfulness, 6(2), 208-216.

- Liberante, L. (2012). The importance of teacher–student relationships, as explored through the lens of the NSW Quality Teaching Model. Journal of student engagement: education matters, 2(1), 2-9.

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of educational research, 79(1), 491-525.

- Mashau S, Steyn E, Van der Walt J & Wolhuter C. (2008). Support services perceived necessary for learner relationships by Limpopo educators. South African Journal of Education, 28(3): 415-430.

- Rimm-Kaufman, S.E., Pianta R.C., Cox, J.J., & Bradley, R. (2003). Teacher-rated family involvement and children’s social and academic outcomes in kindergarten. Early Education and Development, 14, 179-198.

- Emmer, E. T., Stough, L. M., & Emmer, E. T. (2010). Classroom management : a critical part of educational psychology, with implications for teacher education. Educational Psychologist, 36,103–112.

- Ingersoll, R. M., & Smith, T. M. (2003). The wrong solution to the teacher shortage. Educational leadership, 60(8), 30-33.

- Hall-Kenyon, K. M., Bullough, R. V., MacKay, K. L., & Marshall, E. E. (2014). Preschool teacher well-being: A review of the literature. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(3), 153-162.