Poor, relatively speaking

African governments agree that education is important for overcoming poverty and for increasing equity among social groups. The continent’s leaders have therefore pledged to provide free quality education to children in their countries and have committed to monitoring progress towards these goals. One of the fruits of these commitments has been an increase in the availability of local and international education data. However, the temptation to rank countries based on the results of standardised tests has proven too hard to resist. This traditional focus on so-called ‘league tables’ has been heavily criticised for ignoring the influence of a child’s socio-economic background on test performance, especially as access to education has expanded. Children of the rich have many advantages over children of the poor. This is because families of lower socio-economic background are often unable to provide their children with the additional resources that may improve learning. The influence of socio-economic background has not always been factored into the conversation about the performance of African schooling systems.

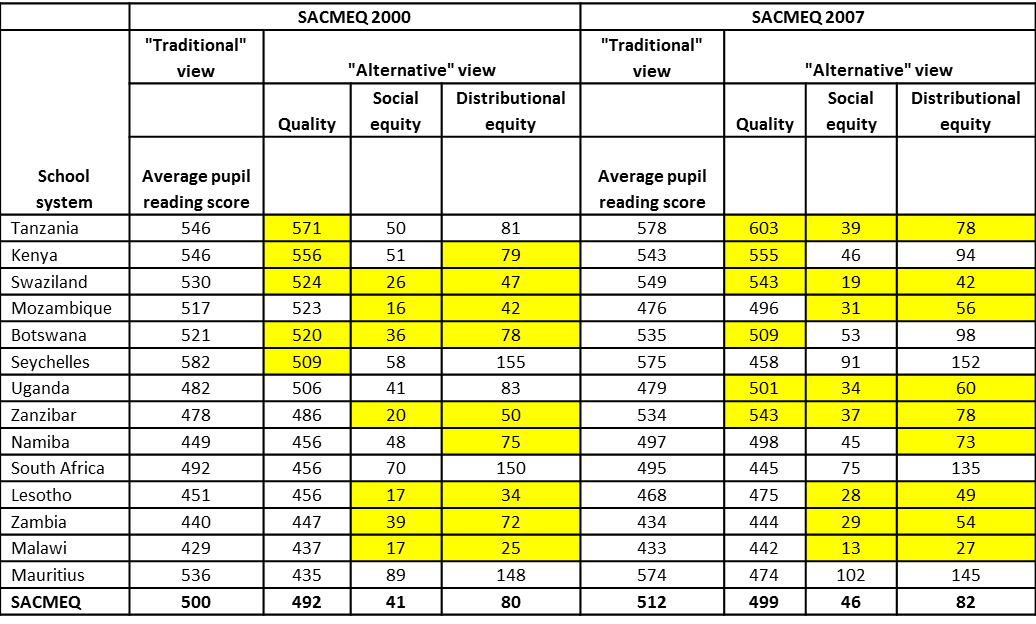

In 2004, researchers at the International Institute of Educational Planning (IIEP) proposed an alternative lens to measure the success of an African education system which recognises the influence of learners’ socio-economic status. In an article that was published in the 2004 IIEP Newsletter, they presented the framework for this ‘alternative view’ based on data from 2000 which looked at Grade 6 learners in 14 African education systems that formed part of the SACMEQ[1] group of countries. In this article, we update the results using data from 2007 and discuss progress made. The original article defined success as based on three criteria:

- Adjusted Quality: This was the achievement level after adjusting for the influence of the socio-economic status of the learner. By setting aside socio-economic status, a clearer picture of the actual contribution of the schooling system in and of itself could be determined.

- Social Equity: This was the extent to which achievement gaps were related to differences in socio-economic status among learners in each country.

- Distributional Equity: This was a measure of differences in achievement between the most able and least able learners in each country.

A high performance system was defined as satisfying all three of the following criteria:

- adjusted quality – with average test scores above the SACMEQ group average;

- high social equity– with values for socio-economic status below the SACMEQ average;

- high distributional equity – with line lengths below the SACMEQ average.

The table above reveals much about how traditional views (based on unadjusted average pupil reading scores) and alternative views (adjusting for quality, social equity and distributional equity) about school system performance can deviate. Values highlighted in yellow in the table show where one of the three criteria was fulfilled. The first observation from these results is that in 2007, the Tanzanian school system was ranked as the highest based on both the traditional view and alternative view of quality. In both 2000 and 2007, Seychelles was among the top performers based on the traditional view of success, but dropped to sixth position in 2000 and eleventh position in 2007 based on the alternative view of quality. In terms of both the traditional and alternative viewpoints, overall regional performance remained relatively constant between 2000 and 2007, as shown by the average values for SACMEQ in the bottom row. This was because half of the countries in the region showed improvement in adjusted quality and social equity, and half showed a decline.

Although shifts in adjusted quality and social equity were mixed, most countries improved in relation to the distributional equity indicator (where lower values represented greater equity). Also worth noting is that in 2000, only Swaziland satisfied all three benchmarks. In 2007, four education systems (Tanzania, Swaziland, Zanzibar and Uganda) had fulfilled all three, suggesting that quality and social equity can be jointly achieved, even in the midst of rapid educational expansion. South Africa’s unadjusted reading score remained below the regional average in both 2000 and 2007. Although South Africa did not satisfy any of the three criteria in either 2000 or 2007, there was some improvement in distributional equity in 2007 when compared to 2000.

Monitoring progress across countries can be a very useful exercise, provided that comparisons go beyond traditional rankings and include meaningful discussions about how educational policies are equalising opportunities to learn.

[1] The Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality collects cross-sectional data on the quality of primary school education in Southern and Eastern Africa.

* Tia Linda Zuze is a Senior Research Specialist in the Education and Skills Development Research Programme of the HSRC.