The place of translanguaging in multilingual education and assessment

The term ‘translanguaging’ has become popularised in recent literature on bilingual and multilingual education with linguists agreeing that it can benefit learning. However, there are some controversies about what the term means and whether it means more than other well-known terms such as codemixing, code-switching and translation. Here I try briefly to distinguish between two contradictory understandings of translanguaging, relate the term to practices that are already familiar to every bilingual and multilingual person in Africa and South Asia, and offer a pragmatic perspective.

One view of translanguaging is that it is an explicit feature of a Welsh-English bilingual programme, intended to develop high levels of language expertise in two languages (i.e. vertical bilingual development) that will best prepare students for access to higher education and future participatory citizenship. In a second understanding of the term, the focus is turned towards informal (horizontal) bilingual and multilingual practices that foster intercultural collaboration and reduce inequalities in the classroom. We know that, in classrooms across the Africa and South Asia, these two purposes are not mutually exclusive.

Cen Williams first used the term, translanguaging in 1996 to explain the deliberate use of Welsh for part of the lesson and deliberate use of English for another part of a bilingual lesson. Sometimes the teacher will teach a component of a lesson while speaking in Welsh, and students follow this with a writing task in English, or vice versa. This involves a series of highly complex metacognitive and metalinguistic processes and capabilities. Because these occur inside the brain, they are neither audible nor visible, so they are not obvious to monolingual speakers.

The second use of the term, translanguaging, is substantially different. Several linguists, notably Ofelia García and Li Wei (2014) in the USA and UK, have borrowed the term from the Welsh context and used it refer to fluid linguistic practices rather than deliberate alternation between two clearly demarcated standard languages (such as English and Welsh). The second perspective of translanguaging is understood to include informal (horizontal), communicative exchanges common among multilingual people. The emphasis here is on how bi-/multilingual people transgress linguistic boundaries in their normal everyday conversations. It is also on how teachers and students can use these transgressive practices (including codemixing and code-switching) to value students’ diverse knowledges and language repertoires in classrooms.

Several recent classroom studies (e.g. Makalela 2015) indicate that where teachers explicitly encourage students to use their linguistic repertoires as fluid resources, students engage productively with diversity, and their self-esteem and confidence grow. This is particularly important in classrooms where there are socio-economic, cultural, epistemological and linguistic differences, and risk of marginality.

To date, there has been very little research that investigates the long-term educational efficacy of legitimising the use of translanguaging where this remains a largely informal practice in classrooms of Europe and North America. We do not yet know the extent to which validating horizontal language (mixing) practices impact on student learning outcomes across the curriculum, or proficiency in a language like English that acts as a gatekeeper beyond schooling.

What we know

The largest datasets of information about what can be expected from different approaches to bilingual education can be found in the system-wide and multi-country studies of education in sub-Saharan Africa. Informal pedagogies that include horizontal practices of language mixing and code-switching (like horizontal translanguaging) have been the actual everyday practices of most teachers and students in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia for the last 100 years. However, because they have not been regarded as ‘legitimate’, both teachers and students have believed them to be illicit, and they remain spoken rather than written practices. Despite official monolingual or bilingual education policies in these countries, and despite informal practices of codemixing and code-switching (horizonal translanguaging), students do not achieve successful learning outcomes unless certain conditions are met. These include an explicit pedagogy that a) draws clear distinctions between the home (or local) language and the target language of learning; and b) where students learn to use both languages for high level academic thinking, speaking and writing. It is almost impossible to develop academic proficiency in English, French or Portuguese unless students develop high level reading and writing proficiency in both a locally used language and English simultaneously.

What we can do in bi-multilingual teaching and assessment

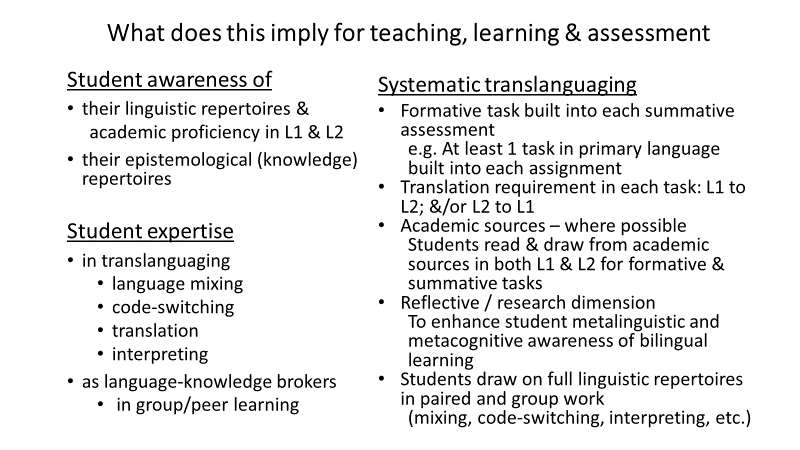

Recent classroom-based research that I have been conducting with university students from highly diverse cultural, epistemological, faith-based and linguistic backgrounds indicates that students gain confidence, find their ‘voice’, and develop strong academic bilingual expertise when teachers develop a focussed pedagogy that includes both the horizontal and vertical translanguaging approaches to:

- build on and encourage students’ linguistic and knowledge repertoires, in spoken and written texts

- recognise that developing bilingual proficiency involves metacognitive and metalinguistic processing (transferring meaning and knowledge back and forth between languages)

- understand writing as a process in which language mixing and code-switching are valued when students are learning and developing their repertoire in a second or additional language

- understand that this is not enough to achieve social justice, equity, or high-level learning outcomes

- adopt a deliberative or purposive approach towards developing high level expertise in translating written information from one language to another (in both directions) over time.

These considerations can be implemented in structured learning activities and assessment tasks. Below I show an example of how translanguaging can be purposefully designed to include both horizontal and vertical dimensions of building bilingual expertise in a classroom.

I encourage students to work through drafts of essays in which they are free to ‘mix’ or ‘blend’ their languages in ways they find useful. However, they are expected to move through various stages of re-drafting, offering translations of specific terms, phrases, expressions, where appropriate, and eventually towards closer proximity to ‘standard’ versions of the target language/s (e.g. Heugh, Li & Song, 2017).

Conclusion: The value of translanguaging in contexts that exhibit high levels of linguistic and other diversities, such as sub-Saharan Africa, is not because this is a new pedagogy. It is valuable because it validates old practices, such as codemixing and code-switching that were recognised long ago by Jacob Nhlapo in the 1940s as normal practices of multilingual people. It does more than this, it rebrands these practices as legitimate in teaching and learning. Earlier seminal research from Southern and West Africa is particularly important for contemporary research on the role of translanguaging in multilingual systems of education. This is because it shows the international community that unless we focus on both the more formal and vertical as well as the informal and horizontal dimensions of bilingual and multilingual learning, we will neither reduce socio-economic and political inequalities nor achieve equitable opportunities for our students’ futures. We need to be careful to avoid the trap of blindly following a narrow North Atlantic view of translanguaging that does not recognise a) its historical links with seminal African research on codemixing and code-switching; and b) that excludes either the horizontal or vertical dimensions of bi-/multilingualism. We need to be smarter. This means focusing on establishing learning environments that value the diverse linguistic and knowledge repertoires that students bring and foster high level academic proficiency in at least two languages.

Author: Kathleen Heugh

Research Centre for Languages and Cultures,

University of South Australia

References:

García, O. and Li Wei. (2014) Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave Pivot.

Heugh, K, Li, X, & Song, Y. (2017) Multilingualism and translanguaging in the teaching of and through English: rethinking linguistic boundaries in an Australian University. In English medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific: issues and challenges from policy to pedagogy edited by Ben Fenton-Smith, Pamela Humphries & Ian Walkinshaw, pp. 259-279. Dordrecht: Springer.

Makalela, L. (2015) Moving out of linguistic boxes: The effects of translanguaging strategies for multilingual classrooms. Language and education, 29(3), 200-217.

Williams, C. (1996) Secondary education: Teaching in the bilingual situation. In C. Williams, G. Lewis & C. Baker (Eds.), The Language Policy: Taking Stock. Llangefni (Wales): CAI.